LIGHTNING-PROOF SKIES: ENGINEERING RESILIENCE INTO AIRCRAFT SAFETY

BEST MAINTENANCE PRACTICE FOR REDUNTANT SYSTEMS

Aircraft encounter lightning strikes regularly, with each in-service aircraft experiencing such an event at least once annually, on average. However, thanks to advanced engineering and design, lightning strikes are generally not a threat to modern aircraft, as they are built to safely handle and dissipate the energy. While lightning strikes possess a considerable amount of energy, modern aircraft are designed in a way that minimizes their effects, ensuring the continued safety of flight operations. This article delves into the phenomenon of lightning, the risks posed to aircraft, design considerations for mitigating these risks, and safety precautions that must be taken by both flight and ground personnel.

LIGHTNING PHENOMENON

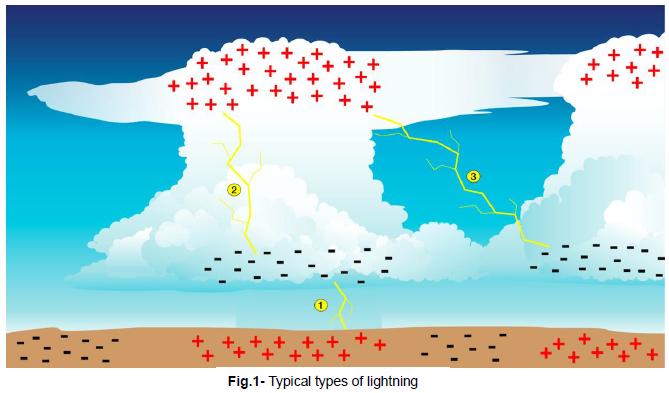

Within storm clouds, the process of thermal convection leads to collisions between ice particles, transferring electrons and causing the accumulation of electrical charges inside the cloud. When the electrical tension between charged areas within a cloud becomes sufficiently high, it overcomes the insulating properties of the air, resulting in a lightning discharge (Fig.1). Lightning strikes can occur between a cloud and the ground ①, inside a cloud ②, or between clouds ③. Statistically, Earth experiences around 44 lightning strikes per second—equivalent to roughly 3.8 million strikes per day. To put this in perspective, that’s like experiencing a flash of lightning somewhere on the planet almost every time you take a breath.

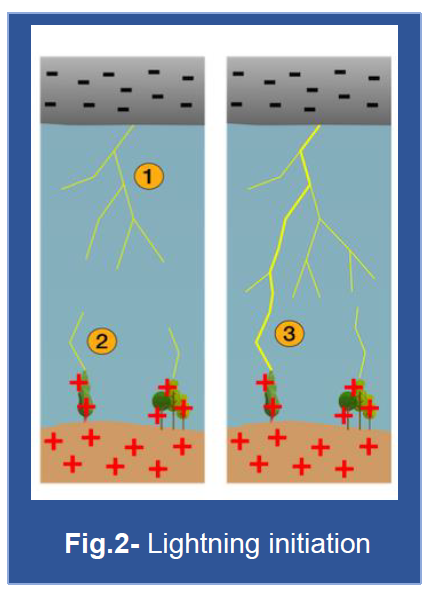

A lightning bolt begins with a column of ionized air (Fig.2) called a ‘leader,’ which typically originates ① from the negative part of a cloud and moves toward a positively charged ② area. Once two leaders meet ③, a high-energy electrical current flow, neutralizing the opposite charges. During a single strike, several successive discharges may occur, with currents reaching as high as 200.000 A and temperatures inside the lightning channel soaring to 30.000 °C.

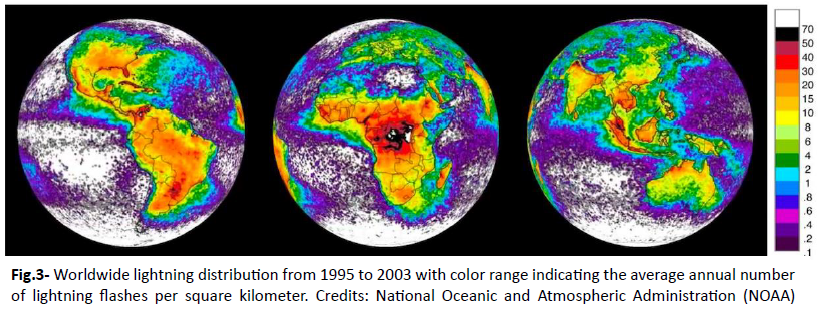

The average global frequency of lightning strikes is about three per square kilometer annually, although this varies significantly by region. Areas such as Central Africa experience far higher rates of lightning activity compared to oceanic or polar regions. The reasons for these disparities include atmospheric conditions, geographic factors, and local weather patterns that enhance the likelihood of thunderstorm formation (Fig.3).

Types of Lightning Strikes

Lightning can be classified into several types, depending on the nature of its occurrence:

- Cloud-to-Ground Lightning: This is the most commonly depicted type of lightning, where an electrical discharge travels between the cloud and the ground. These strikes are typically the most dangerous to aircraft, ground operations, and infrastructure.

- Intra-Cloud Lightning: This occurs within a single cloud, often between regions of differing charge. Intra-cloud lightning is less of a direct threat to aircraft but indicates intense thunderstorm activity.

- Cloud-to-Cloud Lightning: Electrical discharges occur between two clouds carrying opposite charges. Although less common, this type of lightning can still contribute to turbulence and other weather phenomena that pose risks to flight.

Lightning strikes present risks not only to aircraft in flight but also to ground facilities and operations, emphasizing the need for awareness and safety precautions in both scenarios.

AIRCRAFT AND LIGHTNING STRIKES

Though statistics suggest that an aircraft should theoretically be struck by lightning once every thousand years, operational experience shows that in-service aircraft are struck, on average, once per year. This is because an aircraft flying near a storm system effectively becomes a more attractive target for lightning compared to the surrounding environment, especially due to its conductive structure and presence in areas with high electrical fields. The aircraft’s metal body offers a path of lower resistance, making it more likely for lightning to choose the aircraft as a conduit when it passes near an electrically charged region in the atmosphere.

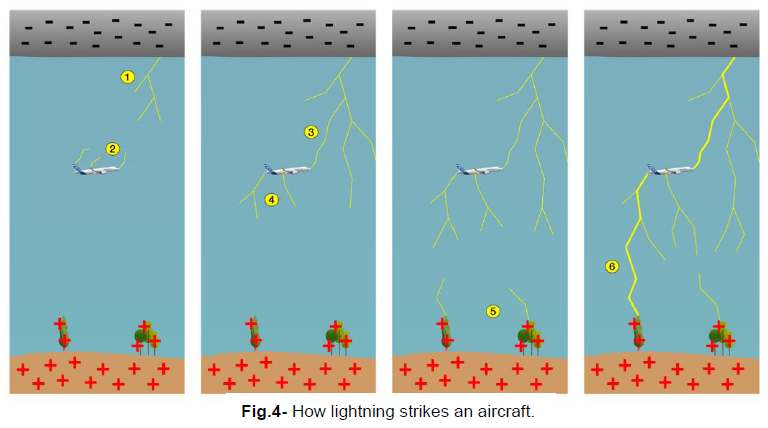

HOW AIRCRAFT BECOME INVOLVED IN LIGHTNING STRIKES (Fig.4)

When an aircraft flies through regions with high electrical potential differences—such as storm clouds (1)—an electrical ‘leader’ may initiate from the aircraft extremities, such as wingtips or the tail (2). If a nearby cloud leader makes contact (3), the aircraft can become part of the lightning channel (4). During these events, the current flows through the aircraft’s frame, exiting at a different point (5) (6). Typically, the entry and exit points are located at sharp edges or extremities of the aircraft, such as the nose cone or vertical tailplane, since these locations are more likely to concentrate electrical energy.

Lightning strikes are most frequent when aircraft are passing through areas of high thunderstorm activity, particularly at altitudes between 5,000 and 15,000 feet. These altitudes often represent the mature stages of thunderstorm cells, which are characterized by significant convective activity and high levels of electrical charge.

AIRCRAFT DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS FOR LIGHTNING PROTECTION

To safeguard passengers and crew, all large aircraft are designed and certified to withstand lightning strikes by internal and military regulatory standards specific to Airbus Defence and Space. This ensures that lightning will not cause significant structural damage or impair critical systems during flight. Lightning protection is achieved through both direct and indirect measures:

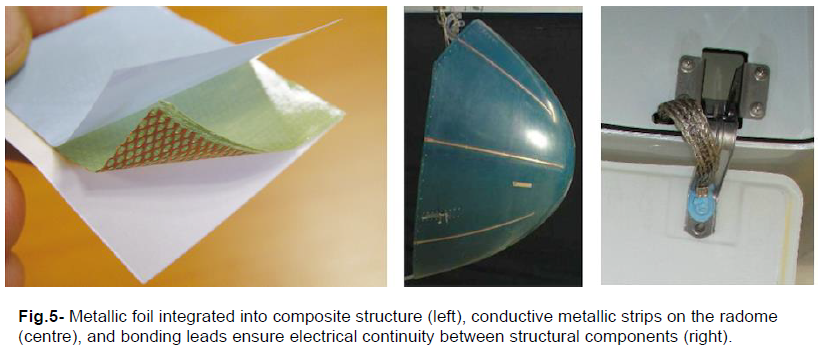

Conductive Structure

The aircraft structure is designed to conduct the electrical current induced by a lightning strike. This includes the use of conductive metallic foils, metallic strips, and bonding leads that ensure electrical continuity throughout the structure. These features allow lightning current to safely pass through without causing substantial damage (Fig.5).

- Metallic Components: Direct effects of lightning on metallic components may include burns, pitting, holes, and structural deformation.

- Composite Components: For composite materials, lightning may cause paint discoloration, punctures, or delamination of fibers, along with damage to integrated conductive elements.

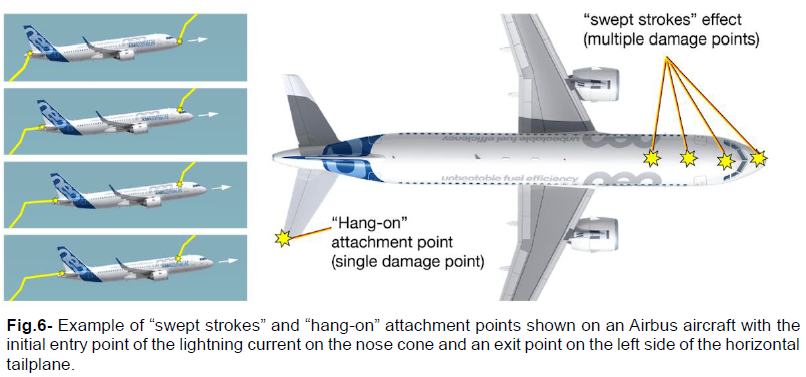

Due to the movement of the aircraft during a lightning strike, attachment points on the aircraft may shift, resulting in multiple ¨swept strokes¨, similar to how a paintbrush moves along a surface, leaving several streaks behind (Fig.6). This can create up to 20 discrete points of contact, each causing varying degrees of damage based on the intensity of the strike.

Shielding and Electrical Bonding

To enhance protection, modern aircraft utilize several measures aimed at safely managing the energy of a lightning strike:

- Shielding: Components like fuel tanks, avionics, and electrical wiring are shielded to prevent damage or interference from lightning-induced electromagnetic fields. This shielding can involve conductive meshes or layers embedded within composite materials.

- Bonding Leads: Bonding involves creating a continuous electrical connection across all parts of the aircraft’s structure, ensuring that electrical currents from a lightning strike are directed safely through the aircraft without interruption.

Additionally, fasteners and other hardware used in joining different structural parts are designed to promote electrical continuity, reducing the potential for sparking and minimizing heat build-up.

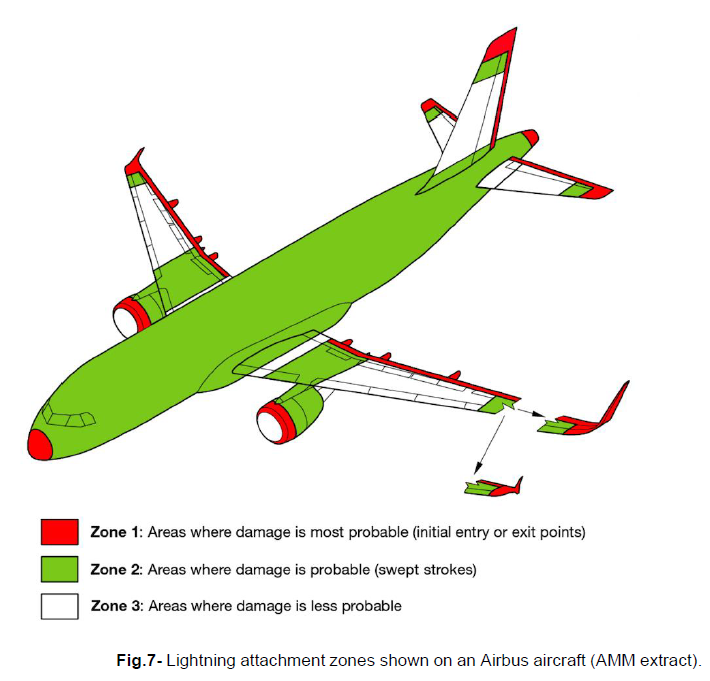

Aircraft Lightning Attachment Zones

Aircraft surfaces are divided into several lightning attachment zones based on the probability and type of lightning strikes expected (Fig.7). Understanding these zones is crucial for determining the right protection measures, ensuring that the most vulnerable parts of the aircraft are adequately shielded to maintain safety during flight. These zones help engineers determine appropriate protection measures and define the area’s most prone to damage. The lightning attachment zones include:

- Zone 1: Areas likely to receive initial lightning strikes, such as the nose and wingtips. These zones require robust protection measures since they often endure the most intense currents.

- Zone 2: Areas where lightning may exit the aircraft or where continuing lightning attachment may occur, such as trailing edges of control surfaces or the vertical stabilizer.

- Zone 3: Areas of low probability for attachment, typically located on the aft surfaces of the aircraft.

Lightning strikes generate strong electromagnetic fields that can induce unwanted transient voltages and currents in an aircraft’s wiring and systems. These induced currents can lead to system malfunctions, such as erroneous readings on cockpit instruments or temporary disruptions in communication systems, which could impact flight safety if not adequately protected against. This indirect effect, known as electromagnetic interference (EMI), can cause malfunctions in avionics or critical flight control systems. To mitigate these indirect effects, redundant systems are employed alongside physical and electrical segregation of essential components.

Electromagnetic Protection Strategies

The following measures are taken to protect aircraft systems from indirect lightning effects:

- System Redundancy: To ensure continued functionality during and after a lightning event, critical systems are duplicated, with each copy shielded and independently routed to minimize the risk of simultaneous failure.

- Physical and Electrical Segregation: Redundant systems are physically separated, often located in different parts of the aircraft, ensuring that even if one system is compromised, another remains functional.

- Shielding and Surge Suppression: Electrical harnesses are shielded with conductive layers that divert electromagnetic energy away from sensitive systems. Surge arrestors are also used to dissipate excess energy, preventing it from reaching avionics or other critical equipment.

- Differential Transmission Lines and Data Management: Differential signaling is used in certain wiring systems to reduce susceptibility to external electromagnetic noise. Software algorithms are also in place to filter corrupted data and maintain system stability.

The complexity of modern aircraft, with extensive electronic control and fly-by-wire systems, requires robust shielding strategies to maintain safe operations in the event of a lightning strike.

LIGHTNING STRIKE PREVENTION & SAFETY PRECAUTIONS

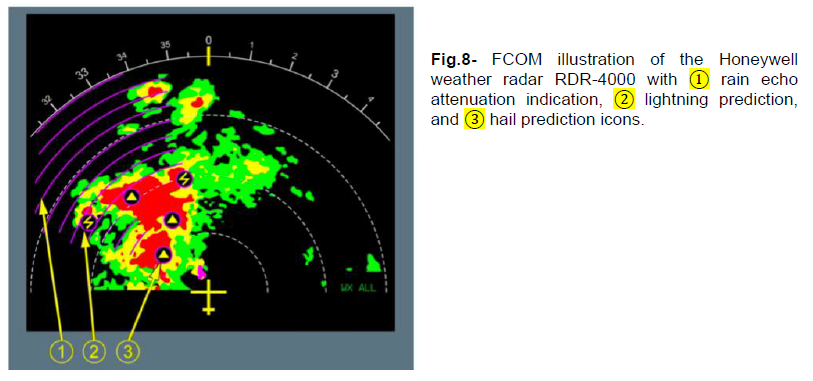

While modern aircraft are built to withstand lightning strikes, prevention remains key. Most lightning strike events occur between altitudes of 5,000 ft and 15,000 ft, or while the aircraft is on the ground. Flight crews can reduce exposure by using weather forecasts, onboard weather radar (Fig.8), and Air Traffic Control (ATC) guidance to avoid areas prone to lightning. For example, during a flight over the Atlantic, a crew used their onboard radar to detect a growing thunderstorm, and ATC helped reroute the aircraft around the storm, successfully avoiding a lightning strike and ensuring passenger safety. Some weather radar systems also feature a lightning prediction function to assist in route planning.

In-Flight Lightning Avoidance Techniques

Flight crews have several tools and techniques to avoid lightning-prone areas:

- Weather Forecasts and Data: Prior to flight, meteorological data is reviewed to identify areas with expected thunderstorm activity. Flight planners may modify routes accordingly to minimize exposure.

- Onboard Weather Radar (Fig.8): During flight, radar is used to monitor storm cells and areas of high convective activity. Advanced weather radar systems can display storm intensity, predict hail and lightning presence, and guide flight crews in adjusting their flight path.

- Air Traffic Control Guidance: ATC plays a vital role in routing aircraft around significant weather systems, providing information on observed or reported lightning activity, and coordinating with other aircraft in the vicinity.

When avoiding a storm is not feasible, pilots may adjust altitude to minimize exposure. Storm cells often have defined vertical extents, and climbing or descending a few thousand feet may allow the aircraft to avoid the most active areas of electrical activity.

Safety Precautions on the Ground

When an aircraft is parked or undergoing maintenance during a storm, specific precautions should be taken to limit the risk of lightning damage:

- Grounding (Earthing): The aircraft must be properly grounded to prevent damage or injury if lightning strikes. Grounding ensures that the current safely exits through a designated point rather than unpredictably.

- Suspension of Maintenance Activities: Maintenance and servicing should be halted during a storm to protect personnel from potential injury. The shockwave associated with a lightning strike can cause substantial harm even if personnel are not directly in contact with metal components.

- Disconnection of External Equipment: Disconnecting external power supplies, air conditioning carts, and other ground equipment can help prevent equipment damage and ensure personnel safety.

Personal Safety Measures for Ground Personnel

Personnel working near an aircraft during a lightning storm should adhere to the following safety precautions:

- Avoid Contact with Metal Components: Personnel should avoid touching metal parts of the aircraft or ground equipment to prevent accidental conduction of electricity.

- Use of Insulated Tools: When working on the aircraft, insulated tools should be used where possible to reduce the risk of electric shock.

- Follow Local Lightning Safety Protocols: Airports and ground handling organizations often have protocols in place for lightning safety. These may include restrictions on operating certain types of equipment during storms and designating safe areas for personnel.

MANAGING LIGHTNING STRIKES ON AIRCRAFT

When an aircraft is struck by lightning, it is essential to follow a structured inspection process to detect any damage and perform necessary repairs. The flight crew must make a logbook entry documenting the event, and maintenance personnel should use this information to guide their inspections.

Post-Lightning Strike Inspection Procedures

Different types of post-lightning strike inspections exist, ranging from a standard inspection to a Quick Release Inspection (QRI), which allows for a reduced scope of checks under specific operational conditions. The QRI is advantageous in operational contexts because it minimizes aircraft downtime, allowing quicker return to service while still ensuring safety. Standard inspections involve a comprehensive examination of the aircraft surface, while QRI focuses on the area’s most prone to lightning strikes.

- Standard Lightning Strike Inspection: This involves a detailed examination of the entire aircraft to detect visible signs of lightning impact, including burn marks, punctures, and delamination. Systems checks are also performed to ensure all electronic systems are fully functional.

- Quick Release Inspection (QRI): This is a more time-efficient approach that targets the most likely areas of impact. If no damage is found, the aircraft may be returned to service for a limited number of flight cycles before a full inspection is mandated.

- One-Flight-Back Inspection: In some cases, a minimal inspection may be conducted to allow the aircraft to return to a maintenance base where a full inspection can be carried out. This approach is strictly regulated and only used under specific conditions.

Damage Evaluation & Repair

Repairs following a lightning strike must adhere to approved standards, such as the Structural Repair Manual (SRM) and other military-specific repair protocols for transport aircraft. Adhering to these standards ensures continued safety and compliance with aviation regulations, providing reassurance that all repairs meet stringent safety requirements. If the damage exceeds SRM limits, repair instructions must be obtained from Airbus D&S (ADS) or an appropriate regulatory authority. Repairs often involve the replacement of damaged panels, reapplication of conductive foils, and verification of electrical bonding integrity.

- Evaluation of Composite Damage: Composite materials are particularly vulnerable to delamination and punctures from lightning strikes. Specialized non-destructive testing (NDT) techniques, such as ultrasound or thermography, are used to evaluate the extent of damage.

- Repair of Metallic Structures: For metallic parts, repairs may include smoothing out pitting, welding, or replacing components depending on the severity of the damage.

Reporting Lightning Strike Events

To enhance industry knowledge, all lightning strikes—even those resulting in no observable damage—should be reported to ADS. This data contributes to ongoing improvements in safety measures.

Importance of Reporting and Data Collection

Lightning strike data is crucial for improving aircraft design and understanding the behavior of lightning interactions with different materials. By reporting all incidents, regardless of their severity, operators help manufacturers refine protective measures and better understand lightning’s impact on evolving military aircraft designs, particularly those with increased composite material usage in military transport settings.

SUMMARY

Aircraft frequently encounter lightning strikes, making it crucial for manufacturers to ensure that these incidents do not compromise aircraft safety. To minimize risk, flight crews are encouraged to avoid areas with high lightning activity, utilizing weather forecasts, onboard radar, and guidance from air traffic control.

On the ground, lightning safety protocols are equally vital. When an aircraft is parked outside during lightning conditions, grounding the aircraft, halting maintenance or ground operations, and disconnecting external equipment are key precautions. Familiarity with local airport regulations and having specific protocols for flight, maintenance, and ground crews is essential for safe operations during severe weather events.

If a lightning strike does occur, prompt and accurate documentation in the aircraft logbook is critical, followed by detailed inspections and assessments according to Aircraft Maintenance Manual (AMM) or Maintenance Program (MP) guidelines. Any necessary repairs must adhere to the Structural Repair Manual (SRM), ensuring thorough resolution of any potential issues.

Airbus DS encourages operators to report all lightning strike incidents, even if inspections reveal no damage. This data enhances industry-wide knowledge and supports ongoing improvements in aircraft safety amidst lightning threats.

INFORMATION

Detailed information on the lightning phenomenon and its effect on aircraft can be found in the “Lightning Protection of Aircraft Handbook” created by Franklin A. Fisher Vand J. Anderson Plumer, available for download on the FAA Technical library.

The standard ED-91A – Lightning Zoning and the SAE Aerospace Recommended Practice (ARP) ARP5414B – Aircraft Lightning Zone, provides information on lightning strike zones and guidelines for locating them on particular aircraft.