COCKPIT CONTROL CONFUSION

INSIGHTS AND BEST PRACTICES FOR ENHANCED PILOT SAFETY

Mistakes in activating the wrong control aren’t unique to the cockpit; they’re a universal challenge across many complex and fast-paced environments. From medical settings, where a nurse might administer the wrong medication due to similar packaging, to industrial plants, where workers might misinterpret controls under time pressure, the potential for “control confusion” is all too common. Even in our daily lives, reaching for the wrong button on a device or selecting the incorrect tool from a set is something many can relate to.

In aviation, however, the stakes are higher, and the potential for operational and safety consequences makes control confusion particularly critical. Inadvertently selecting the wrong cockpit control is an error that any pilot—no matter their experience level, and civil and military context—might face. This article explores the factors that contribute to this type of error, illustrating that even with extensive training and experience, situational pressures and design similarities can lead to unintended actions.

In aviation, however, the stakes are higher, and the potential for operational and safety consequences makes control confusion particularly critical. Inadvertently selecting the wrong cockpit control is an error that any pilot—no matter their experience level, and civil and military context—might face. This article explores the factors that contribute to this type of error, illustrating that even with extensive training and experience, situational pressures and design similarities can lead to unintended actions.

Aircraft systems are designed with resilience, implementing safety barriers that help prevent serious incidents stemming from control errors. However, understanding the triggers and potential impact of cockpit control confusion is key to further strengthening safety measures.

Through a look at common causes, effects, and best practices, this article aims to raise awareness and provide valuable insights to help pilots and technicians reduce the risks associated with related control confusion. These strategies can play a crucial role in maintaining operational safety, reinforcing that while control confusion is an issue across various fields, addressing it in aviation is imperative for the safety of both air crew and passengers.

CASE STUDY

Event Description

The event in question involved an Airbus aircraft during pushback and engine start procedures. The First Officer, acting as Pilot Flying (PF), called the ground crew to initiate pushback and engine start. Following the standard procedure, the PF released the parking brakes. Shortly after the aircraft began moving, the First Officer announced, “starting engine one.” As part of the engine start procedure, the First Officer inadvertently engaged the parking brake handle instead of selecting the Engine Mode (ENG MODE) selector to IGN/START, causing the aircraft to come to an abrupt stop. The sudden halt led to the nose landing gear being dislodged from the tow clamp, causing it to lodge on top of the towbarless pushback vehicle (Fig. 1). This incident resulted in minor injuries to two cabin crew members, who were conducting the safety demonstration at the time. Fortunately, there were no severe injuries among passengers or crew, and all were able to safely disembark the aircraft.

Event Analysis

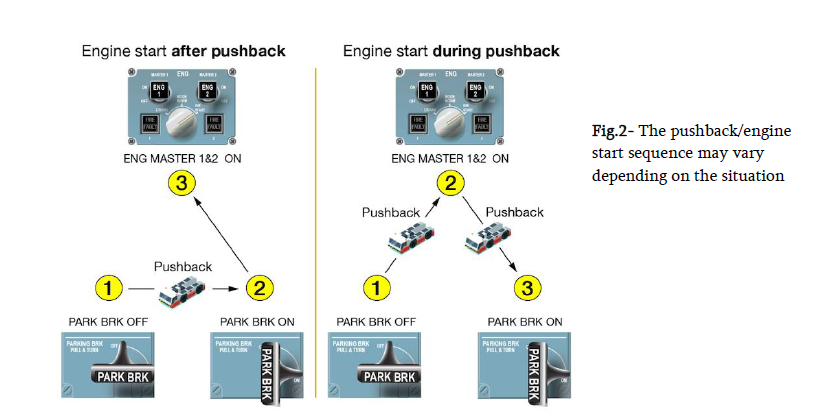

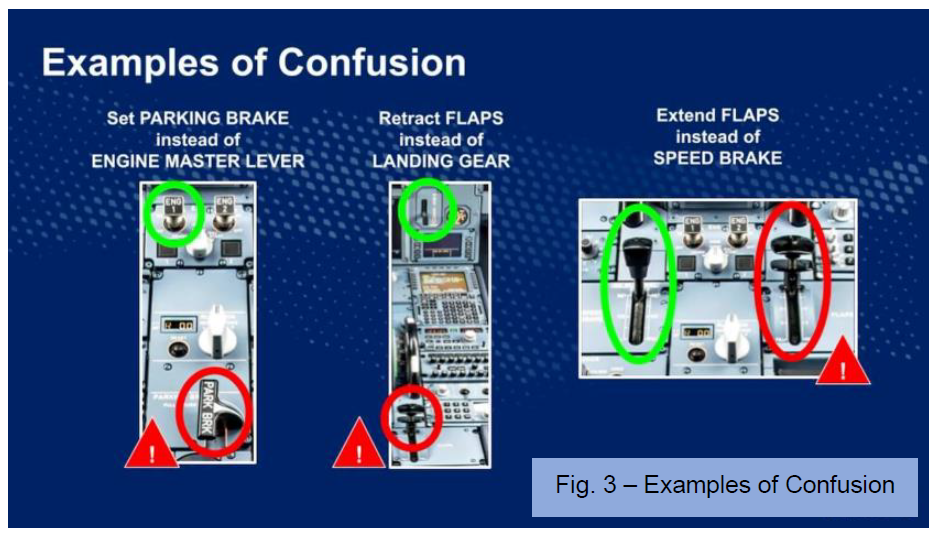

Parking Brake Handle vs. Engine Mode Selector (Fig. 2)

During the engine start sequence, the PF inadvertently set the PARKING BRK handle to ON instead of setting the ENG MODE selector to IGN/START. Both controls are located on the pedestal. The PARKING BRK handle needs to be pulled, turned in the clockwise direction to ON, and released. The ENG MODE selector also needs to be turned in the clockwise direction to IGN/START. Both controls are used in the pushback and start sequence by either (fig.2):

- Setting the PARKING BRK handle to OFF before pushback, and setting it back to ON when pushback is complete, and then setting the ENG MODE selector to IGN/START to start the engine, or

- Setting the PARKING BRK handle to OFF before pushback, then setting the ENG MODE selector to IGN/START to start the engine during pushback, and setting the PARKING BRK handle back to ON when pushback is complete.

The inadvertent selection of the PARKING BRK handle instead of the ENG MODE selector is a prime example of cockpit control confusion. Both controls are located on the pedestal, and their operations are somewhat similar—requiring rotational movements in a clockwise direction. The error made by the First Officer occurred during a routine phase of operations, where the muscle memory and familiarity with frequently used controls can sometimes lead to slips, particularly when attentional control lapses. In this case, the First Officer’s familiarity with the control location, combined with the proximity and similar actions of the two controls, contributed significantly to the confusion.

CAUSES OF COCKPIT CONTROL CONFUSION

Situations and Context

Cockpit control confusion is not restricted to high-stress or high-workload situations. It can happen during routine operations, even to the most experienced flight crews o technicians. As noted, this event occurred under normal operational conditions, which highlights that this type of error is not necessarily related to a lack of knowledge or skill. Instead, it is a “slip” or skill-based error where the pilot’s intended action is correct, but the execution is flawed due to a momentary lapse in attentional control.

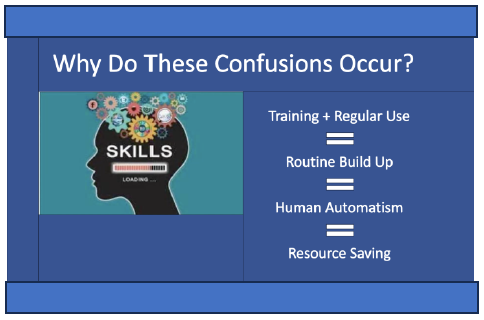

Humans and Routine

The human brain optimizes its capacity by creating routines. When a task is performed repeatedly in the same context, a person tends to perform it automatically, without active, conscious thought. This natural cognitive mechanism allows pilots to handle multiple tasks in the cockpit simultaneously.

However, such reliance on established routines can lead to unintended consequences, such as selecting an incorrect control due to a momentary lapse of awareness.

Skill-Based Errors

James (Human error. Cambridge university press, 1990), an expert on human error, categorizes skill-based errors into two types: lapses (an action that is missed) and slips (an action that is performed incorrectly). Cockpit control confusion is a classic example of a slip—where the intended action was correct, but the execution was incorrect. In this case, the First Officer intended to turn the ENG MODE selector to IGN/START but mistakenly moved the PARKING BRK handle instead.

Contributing Factors

Routines and Overconfidence

Experienced pilots and maintenance personnel, who frequently perform wellknown procedures or routine tasks, are more prone to this kind of error. Their familiarity and well-developed muscle memory around frequently used controls can sometimes lead them to act automatically, without conscious control, thereby increasing the risk of a slip.

Human Factors

Fatigue, overconfidence, distraction, and anticipation are all human factors that can contribute to skill-based errors. For example, anticipating an action by positioning a hand on a control in advance can lead to mistakenly activating that control when the intended action requires a different control. In this incident, the First Officer likely placed their hand on the PARKING BRK handle, anticipating the next action but mistakenly engaging it instead of selecting the ENG MODE selector.

Control Design and Proximity

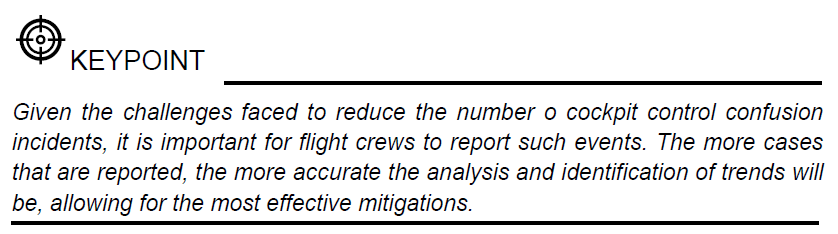

The layout and proximity of controls within the cockpit significantly impact the likelihood of operational confusion. When controls are positioned closely, look visually similar, or require similar movements to operate, the risk of mix-ups increases. For instance, the Parking Brake (PARKING BRK) handle and the Engine Mode Selector (ENG MODE) are located on the cockpit pedestal, both requiring rotational movements to engage. This similarity can lead to inadvertent confusion, even during routine tasks (Fig. 3).

Control confusion often occurs when pilots perform actions on autopilot, relying on muscle memory rather than conscious control. This means that even controls with different shapes and locations can be misinterpreted in high-pressure scenarios or when workload is intense. A documented example of this type of error is the mix-up between the landing gear lever, found on the main instrument panel, and the flaps lever, located on the pedestal (Fig. 3).

Design Factors

Proximity Factors

Proximity also plays a critical role in cockpit control confusion. When a control is positioned closer to the pilot’s seat, it increases the chances of a skill-based error or accidental slip. For example, the Pilot Monitoring (PM) in the right seat is more prone to confusing the flaps lever, positioned on the right side of the pedestal, with the speed brake lever, located on the left side of the pedestal (Fig. 3).

Challenges in Mitigating Cockpit Control Confusion

The main challenge in preventing cockpit control confusion is that these errors are not related to a lack of skills or inadequate training. Instead, they stem from the lack of attentional control when performing routine tasks. Conventional training cannot effectively mitigate such slips since these errors are due to cognitive automation that the brain relies on to reduce workload.

Moreover, redesigning cockpit controls, especially those familiar to thousands of pilots, may not be a feasible solution as it could lead to unintended consequences. Despite these challenges, fostering a culture that encourages flight crews to report cockpit control confusion incidents is vital. These reports help identify contributing factors and potential mitigations, even if the aircraft’s systems already exhibit resilience to these errors.

PREVENTIVE ACTIONS

Reporting and Raising Awareness

One of the most effective preventive measures is encouraging pilots to report cockpit control confusion incidents, regardless of the perceived severity. This

contributes to better understanding the contributing factors and helps develop more targeted preventive measures. A “just and fair” reporting culture within

organizations encourages such disclosures and allows for collective learning.

Best Practices for Flight Crews

The Airbus Flight Crew Techniques Manual (FCTM) offers several best practices for mitigating cockpit control confusion. These include:

- Avoid resting hands on controls: Pilots should avoid placing their hands on any control before it is actually needed to minimize the risk of inadvertently

engaging it. - Visual verification: Pilots should always perform a visual check before activating any control, even if they are highly familiar with its location and action.

- Check the outcome: Always verify the outcome of the action performed to ensure it aligns with the intended action.

- Increase attentional focus through callouts: Some operators have implemented additional callouts, such as the PF pointing at the ENG MODE selector and announcing “ENG MODE SELECTOR” before using it. Such practices help increase active attention among flight crew members.

SUMMARY

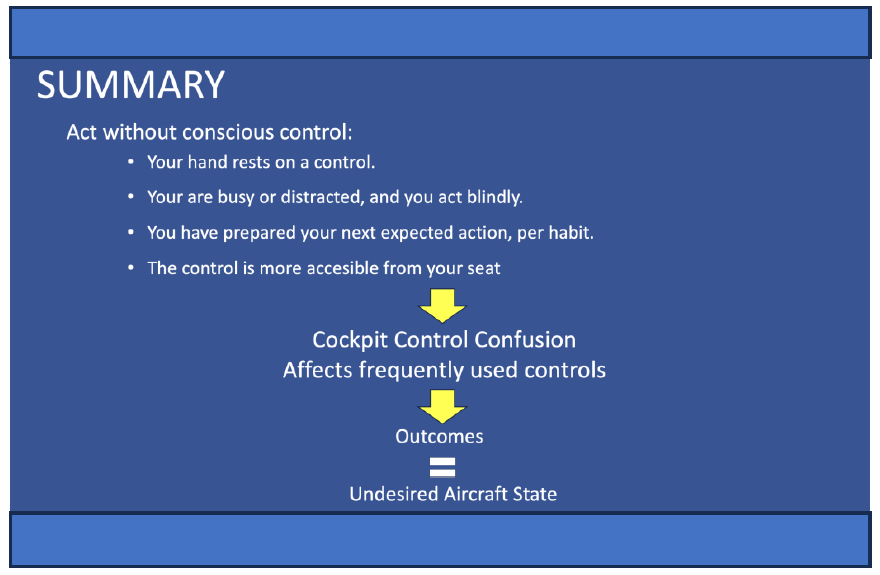

Cockpit control confusion is a subtle yet significant risk in aviation, impacting pilots of all experience levels. This phenomenon doesn’t stem from a lack of skill or knowledge but rather from the human tendency to perform routine actions automatically. Factors like fatigue, overconfidence, distraction, and anticipation can disrupt attentional control, leading to inadvertent errors, especially when controls are similar or located close to each other. Interestingly, these errors aren’t unique to aviation—they’re common in other high-stakes professions, where routine tasks under time pressure can lead to similar mistakes.

Mitigation strategies focus on awareness and procedural discipline. Pilots are encouraged to visually verify controls before activation, monitor the result of their actions, and use standardized callouts to maintain focus. Proactive reporting and analysis of cockpit control confusion events also help in identifying trends and preventing recurrence. Aircraft systems, built with resilient safety barriers, offer added protection against potential consequences. By fostering a conscious approach to every action and a strong culture of vigilance, the risk of control confusion can be minimized, ensuring safer operations for all.